The Dangers of Superficial Activism

Contributed by Kayleigh Bryant-Greenwell

Those that know me, especially those dedicated to the antiracist movement in museums, will likely find this post surprising and uncharacteristic of my practice. As a staunch supporter of social justice and changemaking in museums, it is very “off-brand” for me to affirm the limits of museum activism. Truthfully, I do believe museums can make a difference and more importantly that it is our duty to try. I am, nonetheless, writing this post on the boundaries of museum activism.

I was recently on an email chain conversation about the human rights crimes being committed at the border. A group of museum changemakers, we were discussing the damnable silence of museums on the issue. A group member wanted to end the silence with a social media post both condemning the atrocity and claiming a call to action for museums at large.

While I wholeheartedly support the effort to end museum silence—in silence we are complicit—this proposed effort gives me pause. We’re talking about the horrifically cruel and inhumane separation of children from their families upon entering the U.S. It is sickening and it is wrong.

But what is the call to action for museums?

The call to action as seen in Saturday, June 30th’s March was: reunite families and never separate them or any others ever again. The March served to demonstrate an angered public; but by the time it happened, the Trump administration had already enacted an executive order to cease forced separations, at least temporarily, because that's not the endgame. The oppressive regime in power is actively rolling back human rights towards the goal of increased power and control. Their endgame is closed borders. So within museums, what is ours?

I point to the limitation of ineffective activism in museums in this specific situation, not to diminish the spirit of activism in museums. In fact, I want to see activism greatly expanded within our field. But I want true activism. Activism that is centered in action.

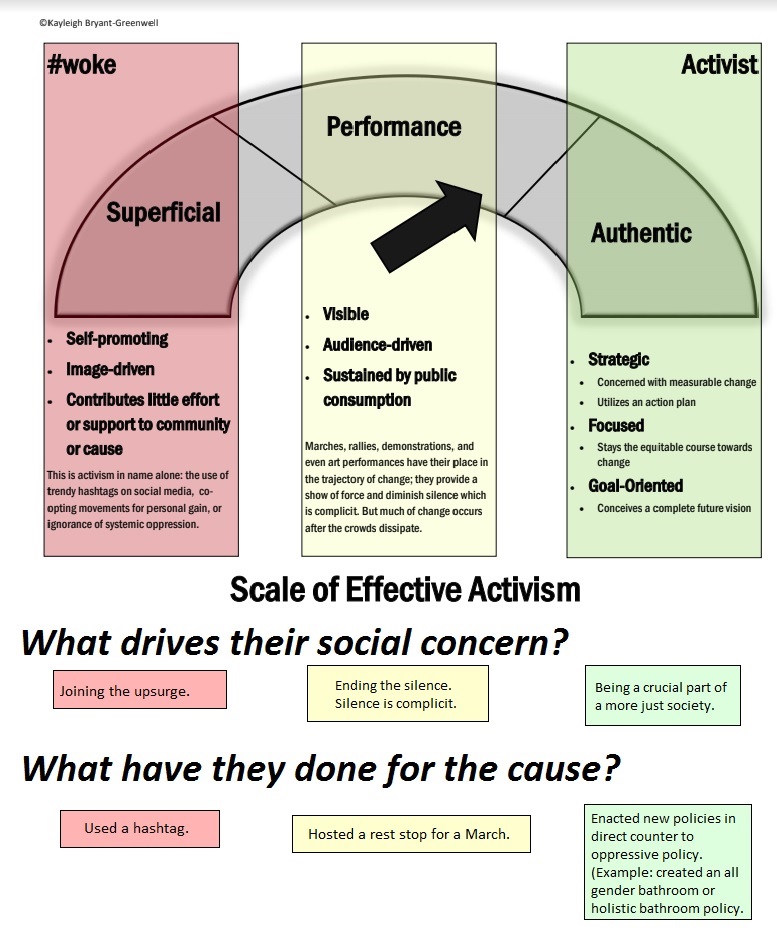

Unfortunately, I feel that most museum activism lies on The Scale of Effective Activism, somewhere between Superficial and Performative activism (see chart below).

Performative activism is highly visible, highly praised, but empty of strategy and impact. It is marches, rallies, viral hashtags, and grand displays of social cohesion around an issue. These efforts do not have a measurable impact of change. As the great activist organizer Saul Alinsky noted in his seminal Rules for Radicals, “Communication on a general basis without being fractured into the specifics of experience becomes rhetoric and it carries a very limited meaning.”

Even worse, Superficial activism—coopting the “brand” of activism without context or steps towards enacting internal or external change within the museum—serves to raise the visibility or popularity of the museum without any effort towards the cause. Alinsky dedicates an entire chapter in Radicals, “The Education of an Organizer,” on warning against the proliferation of organizing in name alone. He cautions, “They were radicals, and they were good at their job: they organized vast sectors of middle-class America in support of their programs. But they are gone, now, and any resemblance between them and the present professional labor organizer is only in title.” To paraphrase Alinsky, tactics must always follow the communicated idea of change.

While it is important to be outraged and vocal, and there will always be a place for some Performed activism, we must consider the impact of these activist efforts. How do these efforts affect the opposition?

Do these efforts move the needle?

In our angered, empowered masses we have yet to effectively communicate to those who continually diminish the humanity of others. We are speaking in completely different languages. Without a radical action plan, our shows of force are dismissed as unimportant and ineffective.

In progressive Marches we speak in a language of “rightness, fairness, justice” while our opposition, in executive orders, policy change, and official mandates, speaks in a language of realized power unthreatened by words. And yet, we applaud every pithy protest sign we painstakingly create, as if we’ve achieved change, whereas we’ve frankly only communicated unrest, which is only enacted the first step towards change. The difference between working towards change and change is a lived experience: a constitutionally-protected marriage, a chance at a new life in a new land, the freedom to control your own body.

We cannot live in an illusion that museums can fix the world. Superficial and Performative activism can only provide an illusion of change. As illustrated in the Scale of Effective activism below, Superficial activism serves to provide the look of progress alone. Performative activism provides a sense of the magnitude of resistance, but doesn’t inherently provide changemaking action.

We must recognize these distinct versions of activism to truly understand the logistics of changemaking.

Museums can, and as MASS Action points out in the toolkit, museums should, sit somewhere between Performative and Authentic activism on this scale, and some may even achieve fully-realized change in Authentic activism. But in order to do so, we must recognize the progressive museum’s place within this trajectory.

Change is strategic. Justice is strategic.

When we eagerly take up activism in visible but actionless ways, we diminish the cause. When we jump to labeling ourselves “woke” without centering our practice in Social Justice and Critical Theory, we dilute our knowledge base. Mistakenly, we convince ourselves that we’ve done enough, when we’ve only done something.

Justice isn’t about “doing something,” it’s about doing the right thing. We are empathetic professionals. When we see the atrocities at the border we are inflamed and eager to start “doing something.” And of course museums can do any number of somethings (see examples below) in this border chaos and the resistance at large. Alinsky wrote, “The organizer knows that the real action is in the reaction of the opposition.” Authentic activism considers the endgame: protecting, expanding, or officializing human rights, not simply raising voice against the infringement of rights.

Effective Authentic activism demands us towards strategic, focused and goal-oriented action. We need our efforts to be tactical in order to be effective. Our future selves and loved ones don’t need our superficial activist distractions. They need real change.

If our goal is true justice we can’t continue to distract with all the unimpactful “somethings” we do. The cause isn’t over when we’ve accomplished something.

Yes, be courageous and radical and outraged. Be vocal and visible about it. But keep action at the center.

Here are two quick questions to ask of your institutions about their activist efforts:

Kayleigh Bryant-Greenwell is a Washington, D.C. cultural programmer and strategist with over 10 years of GLAM experience devoted to exploring ways to engage with marginalized audiences through art, museum, and social justice practice. As a DEAI facilitator, she is a contributor to national initiatives towards increasing equity and inclusion in museums including: MASS Action, The Empathetic Museum, and the inaugural National Summit for Teaching Slavery. She moderated the keynote conversation on education and equity for the American Alliance of Museums 2018 Annual Conference in Phoenix, AZ, with Suse Anderson, Donovan Livingston, and Frank Waln. As an education specialist with the Smithsonian Institution National Museum of African American History and Culture, she curates participatory public programs focusing on social justice issues, which empower museum audiences to share their own ideas and strategies towards equity. In 2015 she launched the inaugural year of the National Museum of Women in the Arts’ Women, Arts, and Social Change initiative, bringing in over 600 new audience members to the museum’s advocacy programming. Her writing is featured with Americans for the Arts, the American Alliance of Museums, and the National Art Education Association’s Viewfinder: a journal of art museum practice.